The two poles of our identity

Even in ancient times, Chinese philosophers asked themselves whether humans were good or evil:

Mong Dsi (or Mengzi; around 300 BCE) says that human nature is good: “The natural instincts carry within them the germ of goodness … If one does evil, the fault is not in his disposition. … The feeling of compassion is inherent in all people, … love and … wisdom are not instilled in us from outside, they are our original possession.” (Höffe, Otfried: Lesebuch zur Ethik.)

Hsün-Tzu (or Xunzi; around 250 BCE) says that human nature is evil: “Human nature is evil, and what is good in man is the result of his endeavours. Our human nature is such that we are interested in material gain from an early age. If man gives free rein to this interest, then strife and robbery arise. … From an early age, man feels envy and aversion.” (Höffe, see above)

In the Age of Enlightenment, Rousseau and Hobbes follow the same pattern. Why the questions about who we are, about human nature? Well, because everyone is subject to it and needs a certain understanding of it: Because everyone tries to optimally control their own behaviour and decisions and to be able to assess the actions of others, e.g. in education, in business, in the family, etc. In this respect, clarification provides information about how one should live.

The inscription above the ancient Greek temple of Delphi ‘Gnothi se auton’, i.e. ‘Know thyself’, is a call for profound self-knowledge, which is decisive for a fulfilled life. This does not only mean material well-being, but also a successful spiritual life that answers the question of meaning and through which people realise their destiny.

On the ‘evil’ part of human nature: By way of introduction, Georg Büchner should have his say in his Letter on Fatalism: ‘What is that in us which lies, murders, steals?’

Wilhelm Busch comments ironically on the negative side of human nature:

“Virtue wants to be encouraged,

Malice can be done alone.“

(Wilhelm Busch: Plisch and Plum)

The Portuguese monk (co-founder of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro) Manuel de Nóbrega wrote in 1559:

‘In the beginning of the world there was only murder and manslaughter.’

(Ben Kiernan: Earth and Blood, p.9)

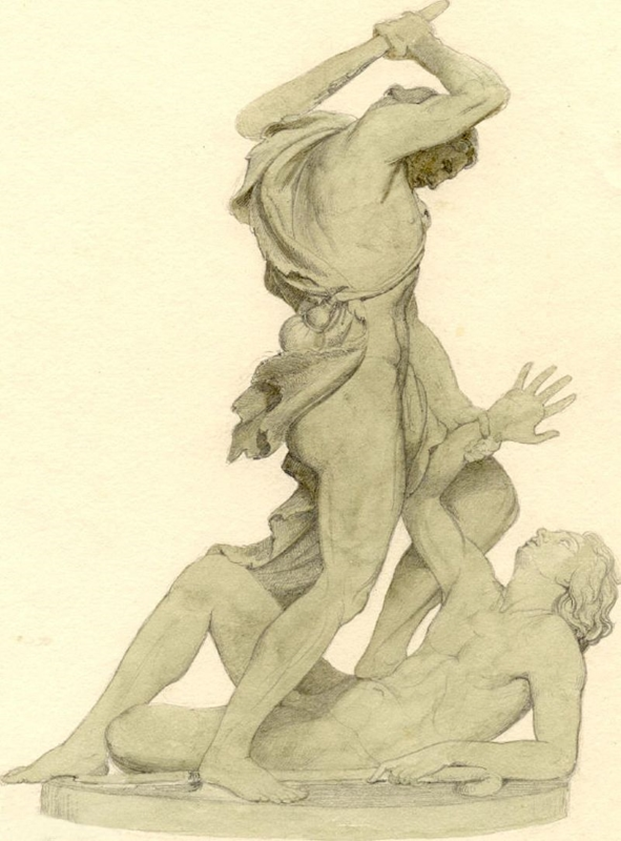

Herrmann Knaur: Cain and Abel group. 1845 Stadtgeschichliches Museum Leipzig, no. 107b. Wikimedia Commons.

The story of Cain and Abel symbolises that the use of violence stands at the beginning of human history and is therefore part of the fundamental nature of human software. Abel symbolises the software part of the human being in which the spiritual part (from ‘above’) of the soul dominates, while Cain represents the part of the human being that is dominated by earthly instincts. The holy book of Judaism, the Tanakh (Christian term: Old Testament), states in this regard:

‘”every desire of their heart was only evil forever.’ (Genesis 6)

But we are called upon to become masters over this demon, and most importantly, we are also empowered to do so:

‘”sin has a desire for you, but you rule over it.’ (Genesis 4)

Binary identity

In the drama ‘Closed Society’ by French writer Jean-Paul Sartre, three people find themselves trapped in hell after their physical death due to their earthly sins, constantly harassing each other and getting on each other’s nerves: ‘Hell is [always] the others.’

Sartre’s play ends with the protagonists’ hopelessness; they don’t know how to get out of this hell and resign themselves to it. Garcin says: ‘So – let’s get on with it!’ But he is wrong, there is a way out. It consists of recognising the ego as such and as a control programme from ‘below’ and then deactivating it step by step by observing and countering.

A top-class professional footballer, who was banned from playing several times because he had bitten opponents, was asked why: “I can’t explain it. It just happens, there’s such anger in me.” (Spiegel 41/2014).

He didn’t recognise the reason, but at least he lifted a corner of the veil. The way out is to recognise ‘hell’ as the almost impenetrable fog that wants to prevent the person from seeing beyond the surface to their spiritual core. Hell, the instinctual soul, the instinct of self-preservation, egoism, this hell is the exclusive view of the merely external otherness of man in relation to other people.

The view of the fingers of a hand feigns their difference, which actually exists on the physical surface level, although their existential essence is their unity, embodied by the common bloodstream, without which the hand could not exist at all. This surface programme – Goethe calls it Mephisto – wants to prevent the ‘deep view’ (buddh.), the view of the true essence of man, of his inner light, of the origin of ‘his’ ideas, of his spiritual likeness, of his inner voice, his gut feeling, his conscience.

In the Odyssey (Fourth Canto 265, 271 ff.; Eighth Canto 492 – 495, 512), Homer attempted to depict these two poles of actual humanity through the image of the Trojan horse by completing the physically actual surface of this wooden figure with the actual invisible truth of the horse. The difference between this literary image and living human beings is that, in Homer, both sides remain on the material plane, whereas in human beings they are vertically opposed to each other, i.e., as matter and spirit.

Man’s halved, purely material view of other people – and of himself – the view of non-unity is the prerequisite and cause of the automatic, unconscious and as if self-evident maxim of self-preservation, of ego-life and the racist and at least egocentric lifestyle derived from it, which has lost nothing of its central role in life since Cain and Abel.

All religions castigate this insanity of the Trojan viewpoint of the exclusively earthly-material and therefore egocentric life, without people listening to them. In Judaism and Christianity, for example, the critical references are as follows:

‘Depart from man who has breath in his nose; for what is he to be esteemed?’ (Is. 2, 22)

‘A man sees what is before his eyes, but the Lord looks at the heart.’ (1 Sam 16:7)

“Now I learn the truth that God does not look at the person.’ (Acts 10:34)

The intelligent, conscious view of the spiritual soul in man is that of ‘the inner voice of the Godhead’ (Gita XVI, 24), of its likeness (Gen. 1, 26 f.), of intuition, of the fact that one ‘only sees well with the heart ’ (Saint-Exupéry: The Little Prince). It is the prerequisite and basis for giving meaning to human life and the associated freedom from suffering:

‘Seek ye first the kingdom of God [spirit, intuition, inner voice], .. and all things shall be added unto you.’ (Mt 6:33)

‘My God, I cried out to you, and you healed me.’ (Ps. 30, 3)

‘Though a thousand fall by your side … it will not fall on you.’ (Ps 91:7)

In Hinduism and Buddhism in particular, the perspective of liberation from suffering occupies a broad or central place. In Christianity in particular, it is not to be understood as a goal, but as a consequence of the absolute commandment, the ‘most noble’ (Mt 22:38), namely ‘to love your Lord God’ (23:37), i.e. our inner voice, our spiritual soul.

Freedom from suffering not only comes immediately when we embark on the spiritual path, but usually beforehand! It is noticeable that, in retrospect, although painful events did occur, they either had a harmonious end (inexplicable rescues) or were purely mental torments and had no material substance.

However, by distracting from the inner unity of all people, the ego wants to consolidate the material view of the outer otherness. This is the only way it can maintain the egocentricity of the self-preservation software towards others. This is why hell is meticulous in ensuring that love remains limited to the physical ‘neighbour’ and is never extended to strangers (parable of the Good Samaritan), asylum seekers, foreigners, bad neighbours or even enemies (Sermon on the Mount: Mt. 5:44). For that would be to reduce self-love from 100 % to 50 % and to extend Samaritan love, which refers to everyone else, i.e. to love them ‘as yourself’(Mt 22:39).

The Islamic mystic Rumi tells the famous story of the parrot in the cage on the subject of ego reduction:

A merchant had a beautiful parrot in a cage. The man wanted to go on a business trip to India and asked all the people in his household what he should bring them. He also asked the parrot for a souvenir. He asked the merchant to tell other parrots there in India about the situation he was in in this cage and that he would like them to tell him what a solution might be for him. The trader promised to pass this on.

When he arrived in India, he met some parrots and made the request. Immediately after hearing this, one of them fell to the ground dead.

When he returned home, the traveller told his parrot what he had heard. When the parrot heard this, it fell dead on the floor of its cage. The merchant was deeply saddened and took the bird out of the cage. It suddenly spread its wings and flew up a tree. He explained the deceptive manoeuvre to the astonished man: the parrot in India had faked its death to signal to the prisoner that he too should ‘die’ in order to finally be free. (Rumi: Mesnevi I, 1556 – 1920)

rfcansole Can Stock Photo csp 17167163

For all living beings, the basic control of their behaviour is not their own consciousness, but the background programme of survival, that of self-preservation. This basic egocentrism applies to microorganisms, plants and animals without exception. The human mammal is the only living being that has a second basic programme in addition to the animal programme. This second control, in addition to self-preservation, is that of all-preservation.

In this respect, his behavioural control basically consists only of the influx from ‘below’ (egocentric self-love) and that from ‘above’ (altruistic self-love and love of others). Man is therefore both materially and spiritually controlled and his behaviour is either divine or animalistic, depending on the proportion of control by the instinctual or spiritual soul.

It is immediately obvious that if all people were primarily concerned with the preservation of all others – within the scope of their personal, local, financial, ecological and physical possibilities and also taking into account their own security – then the preservation of the individual and that of the whole would be comprehensively ensured. However, since its appearance on the stage of world history, Homo sapiens has only followed the programme of its own preservation. For this reason, the first wisdom writings appeared around 3000 years ago to describe the second spiritual half of behaviour control, the preservation of others – in all religions. In Christianity, for example, we find the parable of the Good Samaritan and Jesus’ admonition to love one’s enemies.

Man can ‘ do nothing of himself’ (John 5:30); at the level of the question of existence, he is not a recipe maker, but only a user of both recipes. This self-determined control of his own destiny consists of using his free will to set in motion the mixer lever of his consciousness between ‘above’ and ‘below’. This enables him – at least in principle – to determine the distribution of material and spiritual impulses. His consciousness is the place for this decision-making lever. However, despite the creation story, despite the Sermon on the Mount, despite the Koran, despite the Bhagavad Gita, despite the Tao Te King and despite the Buddhist Noble Eightfold Path, the proportion of material orientation and self-preservation among humans is probably 99%. To use the irony of Wilhelm Busch again: ‘Virtue must be acquired; wickedness can be done alone!’

The free will of man has the mixing valve in his hand and can (more or less) freely decide whether and how much influence he gives to the respective influx in his consciousness. Of course, this presupposes that he is aware of this existential situation, which is usually not the case. Until then, his free will only exists as a potential. However, it is crucial that he can learn to detach himself from pure instinctual control. He is then in a position to consciously detach himself from this and give space to his intuitive guidance in every decision-making situation. The symbol for this is the confrontation with the two trees in paradise: The fact of having to decide in favour of one of them has not changed to this day. In this respect, man finds himself in an intermediate position between above and below, between animal and spiritual consciousness. Everyone is, so to speak, both a Luci-fer and a Christo-fer (ferre: to carry).

“Heaven is within you

and also the torment of hell,

what you choose and want,

you have everywhere.”

(Angelus Silesius: Cherubinischer Wandermann, Book I, verse 145)

His relay share in his behavioural control is qualitatively decisive. To put it in terms of mathematical physics (chaos theory): The flap of a butterfly’s wings triggers a hurricane. However, this flapping of wings requires all of our strength and endurance. While the decisions for self-preservation are practically served to us on a platter, recognising the divine life behind our material life is only the result of an arduous journey.

The human mind (see Forrest Gump below) is only a tool of operative perception, an instrument that receives input and can process it intelligently, but only appears to be independently creative. The fact that it cannot create is a serious insult to the ego, and even more so to the ego of the natural sciences, for example. They imagine that they can create all sorts of things with their minds, that they can play God, for example through human design or cloning. The misunderstanding is that the calculation and linking operations of the mind with their intelligent results simulate original self-control.

This applies first of all to the material dimension, such as the computer-controlled forecasts of meteorologists, which serve the basic programme of self-preservation, for example by predicting the development of the weather for the harvest and by warning of destructive global warming. However, this also applies to the spiritual programme, in which reason is only a subordinate instrument. For when, for example, Luther castigates the Vatican’s indulgence fraud or Professor Küng the Pope’s claim to infallibility, ‘their’ ideas were not products of their intellect: Both may have used their minds, but Luther’s mind was recognisably controlled from ‘above’, among other things in his fight against that fraud to the detriment of the faithful. In contrast, the Pope’s control, with his egocentric infallibility and desire for power over others, came from ‘below’.

Gandhi, for example, consciously recognised his resistance to the tyranny of the British Empire as his leadership through his inner voice for the blessing of the Indian people and used his intellectual abilities accordingly.

Puccini, for example, expresses this through his confession: “I do not compose. I do what my inner voice tells me to do.” He thus makes it clear that he is aware that his ideas – his ideas – are not his own.

The control by the programme of self-preservation with xenophobia, racial hatred etc. is not primarily a characteristic of the person and does not only exist as ancient genocide (e.g. Caesar against the Usipetians), as medieval anti-Semitism or modern holocaust as well as the many other genocides, but as an animal characteristic of being human in general. Cain and Wilhelm Busch send their regards.

Man seems to have creative power, as can be seen from his decisions in favour of wars or the destruction of the climate, but also, on the other hand, from medical, technical and social progress. However, these examples are merely decisions between two predetermined paths. However, if we compare murder and manslaughter on the one hand and, on the other, saving lives in emergency situations at the risk of one’s own life – the latter against absolute self-preservation – these are decisions between impulses from ‘below’ or ‘above’. Here, people can choose between them – at least in principle. In principle, they can pull the lever upwards or downwards and use their intellect to work out and realise these concepts and even optimise them: Do I build a nuclear bomb, do I found a Red Cross? Do I embezzle money from the club treasury? Do I put my life at risk by extinguishing a forest fire or providing development aid in war zones?

The material vs. spiritual (horizontal-vertical) laws of Cain and Abel were already there before man, he has nothing to do with their creation and can only deal with them. Einstein did not invent relativity, he only discovered it.

The lion in the steppe has only one programme that controls it, the mammalian programme of self-preservation. It hunts, eats, mates, defends its territory, protects its offspring, gathers fresh strength during its rest periods and bites away competitors. It is at the mercy of this programme, it cannot get out of it.

Humans – and this is the difference to mammals – have two programmes. Firstly, he follows exactly the same animalistic programme of self-preservation as the lion, and usually 99% of the time. Beyond that, however, there is the spiritual soul, the spiritual programme of overcoming separation, called love. This type of love is spiritual, goes beyond the two levels of earthly love such as erotic and sympathetic love (see below on love chapter 17) and is based on spiritual insight – through the glove to the hand. Man is the only mammal that can break out of animal control. This second programme is the qualitative difference to the animal. It is there to overcome the first one. It is intended to lead man to his destiny, to self-realisation of the inner divine being, which then lifts him out of the world of suffering. The path to this second programme of consciousness and behaviour – lions know no Samaritans – is the single theme of all wisdom writings of all cultures and peoples.

A commentary on chapter 2:

hannah says:

Your summary and the way you are able to put your perception into words- this is exactly what I was looking for. Describing the indescribable … Thank you! The whole blog is extremely opening – at least for me. I have found words for so much that I couldn’t bring anyone closer to before- the translation was missing.

One thought on ‘Chapter 2: Is man good or evil?’

Thais says:

Un aporte muy interesante. Muchas gracias por la ilustración. Saludos.

Un aporte muy interesante. Muchas gracias por la ilustración. Saludos.